Delivery workers parked their bikes near a cafe in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, Sept. 15, 2021.Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

This article was originally published by The CITY on Nov. 21

After a fast-moving fire in a luxury Manhattan tower called Rivercourt injured dozens of tenants and triggered a daring high-rise rescue, fire officials made clear that the cause was an increasingly common phenomenon — an exploding e-bike battery.

But in one way, the fire at 429 E. 52nd St. was an outlier: an e-bike battery fire starting inside an exclusive high-rise building in an upscale neighborhood.

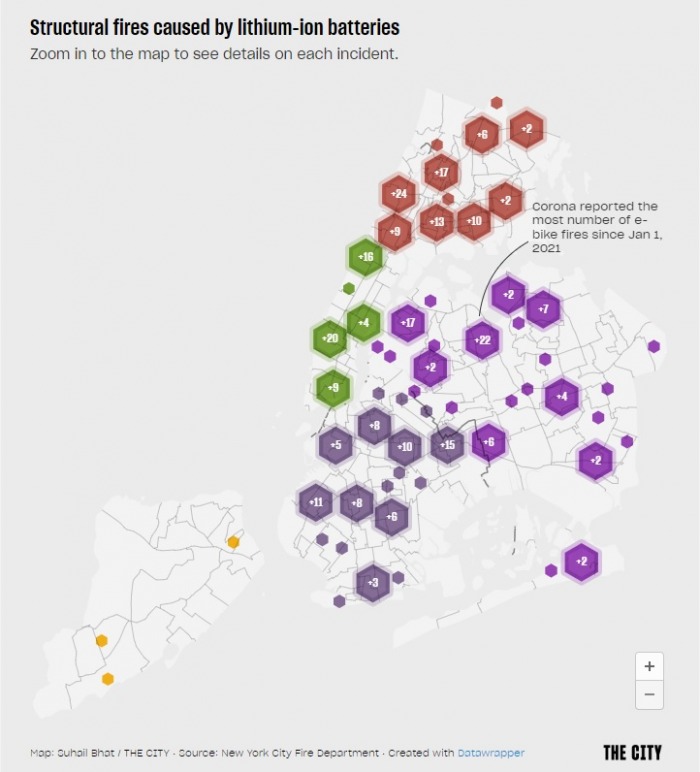

An examination of Fire Department data by THE CITY reveals that, by far, most of these fires are taking place in modest apartment buildings without fancy names or in one- and two-family homes far removed from affluent Midtown East.

As this disturbing trend has unfolded, some neighborhoods in particular — primarily working class areas in Queens, Brooklyn and The Bronx — have experienced more than their share of these conflagrations.

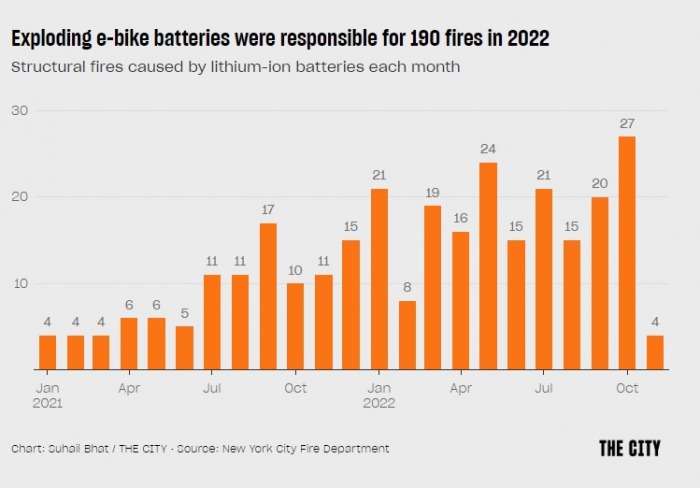

The number of e-bike-related fires took off during the pandemic, coinciding with the growth in riders using battery-powered devices to deliver takeout via apps such as GrubHub and DoorDash. In 2020, the Fire Department determined that 44 fires were caused by faulty e-bike batteries; in 2021 there were 104. So far this year there have been 191.

These fires, triggered by poorly maintained or damaged lithium-ion batteries, have caused 10 deaths and more than 200 injuries in the five boroughs in just the last two years alone.

These fires, triggered by poorly maintained or damaged lithium-ion batteries, have caused 10 deaths and more than 200 injuries in the five boroughs in just the last two years alone.

With such incidents on the rise, THE CITY obtained fire department data that details the location of all 221 structural fires across the city that the FDNY has blamed on exploding e-bike batteries from Jan. 1, 2021 through last week.

THE CITY zeroed in on the neighborhoods with the most fires, focusing on ZIP codes with five or more. We found 81 e-bike fires in 12 ZIP codes, all which were home to high concentrations of lower-income residents. All but eight such fires took place inside residential properties, usually multi-unit rentals or one- or two-family homes. Nine erupted inside public housing apartments.

The median income in all 12 ZIP codes with the highest number of e-bike fires averaged $44,400 — well below the state’s ($71,117) and the city’s ($67,046), THE CITY found. One ZIP code in the South Bronx that saw five fires has one of the lowest median incomes in the entire city: $23,337.

The ZIP codes with the most fires were located in four of the five boroughs in a variety of neighborhoods, including Corona and Sunnyside in Queens, Sunset Park, Brownsville and Bushwick in Brooklyn, Williamsbridge and Morrisania in the Bronx, and the Lower East Side in Manhattan.

Within one ZIP code in Corona, there have been 14 of these fires since Jan. 1, 2021 — the most of any ZIP code in the city. That’s about one every six weeks.

The fires have hit public housing hard. In the last two years NYCHA properties have had a total of 31 e-bike-related fires, particularly in Manhattan neighborhoods with multiple NYCHA developments.

The fires have hit public housing hard. In the last two years NYCHA properties have had a total of 31 e-bike-related fires, particularly in Manhattan neighborhoods with multiple NYCHA developments.

On the Lower East Side, for example, an e-bike fire hit one apartment in NYCHA’s Baruch Houses in April 2021, then another Baruch apartment around the corner in July 2021. A few months later and a few blocks south at NYCHA’s Vladeck Houses, a third fire occurred in May.

This string of calamities for NYCHA tenants peaked with a deadly e-bike fire in August at the Jackie Robinson Houses in East Harlem that killed a 5-year-old girl and her father’s girlfriend, and critically injured her father. Three battery-powered devices were pulled out of the ruins of the apartment where the blaze first sparked.

NYCHA is now considering banning mobile devices powered by lithium-ion batteries from all their properties.

In much rarer instances, the batteries on these micro-mobility devices also trigger fires in commercial locations such as restaurant basements or bike shops.

THE CITY found fires at four restaurants, a supermarket and two delis. In Corona last December, firefighters found themselves responding to two separate fires two days apart at adjacent Junction Boulevard properties — one at an e-bike repair shop, the second at a deli next door that offers delivery service.

Are e-bike batteries safe?

Experts tell THE CITY that e-bikes and their lithium-ion batteries are not, inherently, unsafe. But the way they are commonly being used and charged do present major risks.

Lithium-ion batteries are used in lots of everyday objects, like power tools, vacuums, cell phones and electric cars, with very low rates of failure. The difference with e-bikes is that many of them are being manufactured without safety regulations or third-party testing. Especially in New York, the market has been quickly saturated with a flood of these devices as workers adopt them to meet the growing demand for fast deliveries.

Lithium-ion batteries are part of a larger power system that includes an electronic circuit, battery park, electrical motor and charger. Ideally, every component in this network is well-matched and tested to work in concert, said Ibrahim Jilani, global director of consumer technology at UL Solutions, the 128-year-old product testing and safety company.

But “if that system isn’t working harmoniously, then safety risks occur like explosion and fire,” Jilani said. For example, if a charger pulls power differently than what the battery pack is designed to handle, major issues can occur.

Disposal crews removing a mattress from 429 East 52nd Street after an e-bike battery sparked a fire, Nov. 11, 2022. Hiram Alejandro Durán/THE CITY

New York right now is seeing a “pretty huge influx of e-bikes in the market,” said Leo Raudys, president of Call2Recycle, a nonprofit that recycles lithium-ion batteries.

Overall, that’s a good thing, says Raudys. “They’re excellent climate-fighting transportation and if you’re buying good-quality stuff, they’re very safe. They’re really a good thing,” he said.

“It’s the poor quality — you get what you pay for. If you’re going to buy batteries and they’re cheap and they’re on the black market, there’s a much higher likelihood that it’s going to go up in flames.”

At least one model of e-bike — the Ancheer model number AM001907 — has been identified as particularly dangerous and was recalled last month by the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the federal agency tasked with regulating and overseeing the devices.

What exactly causes battery fires?

A proliferation of badly manufactured parts, cheap modifications to existing batteries, poor storage and charging practices and pressures on delivery drivers are combining to create a spike in e-bike battery-related fires.

These blazes are particularly powerful and toxic. When one cell of a lithium-ion battery malfunctions, it causes “thermal runaway,” said Jilani of UL — that’s when a battery cell can’t dissipate the heat being generated inside it.

“It spontaneously ignites,” he said. “Immediately when they catch on fire, it goes into a big explosion state.”

Worse still, one battery in flames can easily ignite other nearby batteries, such as in a room where multiple e-bikes are charging or being stored. And the fires cause popping and white smoke, which is “toxic and highly flammable,” said the FDNY’s chief of fire prevention Thomas Currao at a recent City Council hearing on e-bike battery fire safety.

Additionally “the fire is not over when the fire is out,” Currao added in his testimony. “The battery is still essentially a box of chemicals and it’s not unusual for it to reignite. Once these batteries are damaged or involved in a fire, they may reignite hours or days after being initially extinguished.”

How can e-bike riders stay safe?

The fire department recommends the following tips to avoid battery fires from e-bikes:

- —Do not leave devices unattended when they’re charging, and don’t leave them charging overnight.

- —Buy devices that have been tested by a reputable laboratory, like UL Solutions.

- —Use only the manufacturer’s power chargers and batteries made specifically for your e-bike.

- —Keep batteries at room temperature and away from any flammable objects.

- —Store your bike away from doors and windows that block exits.

Raudys of Call2Recycle said it’s important to replace batteries when they are damaged, or even possibly damaged. Similar to how bike helmets should be replaced after a crash even if they are not visibly damaged, he recommended riders get new batteries after any accidents.

“If you took a pretty bad fall, you know, you’re running a risk that you damaged the battery as well” he said. “You should err on the side of caution and probably replace that battery.”

Why are delivery workers at high risk?

But following these best practices is tough — and expensive — for workers under the gun of fast-paced, app-based delivery demands.

Los Deliveristas Unidos recently invited fire department officials to discuss safety issues after a spate of fires linked to e-bikes ignited calls to ban the equipment. The delivery workers who met with the FDNY this summer shared how they store their e-bike batteries — and got alarming feedback from fire safety experts.

Two delivery workers, Manny Ramírez and Antonio Solís, who brought their equipment to show fire department officials, were surprised to learn that several of their batteries were not UL-approved.

A sticker showing a Deliverista raising their fist adorns the battery of an e-bike, Oct. 3, 2022. Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Professional e-bike riders told THE CITY that getting UL-grade e-bike batteries, which are manufactured for recreational and not for commercial use and retail for more than $900 each, is a challenge. And charging the batteries as recommended — under supervision, not overnight and away from flammable objects, windows and doors — is also daunting for delivery workers who ride their e-bikes continually during long work days.

Ramírez said his wife and roommates – all of whom are delivery workers – charge their batteries outside the apartment in the multi-family home they rent in The Bronx. But Solís said he had no choice but to charge inside his Astoria, Queens, apartment.

One delivery worker, Sergio Ajche, of Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, said he pays for a charging port in the city — for $125 a month.

Then there’s the fact that the cold weather shrinks the batteries’ use time between charges down to five hours of use instead of eight, said worker Ernesta Galvez of Corona, Queens.

Galvez uses a Bosch pedal-assist bike and battery that she’s relied on for four years, and has two additional, cheaper batteries from a Chinese manufacturer she purchased at a bike shop, she said. Absent better options, she charges the equipment in the apartment she shares with her three children.

“I keep them far away from my kids, and I only charge one at a time,” she told THE CITY in Spanish. “I take all my equipment to the bike shop every six months to make sure it’s in good shape. If anything were ever faulty, I would hand it over to the fire department or the store [for disposal] without hesitation.”

Many delivery workers said they buy their equipment in bike shops — viewing their purchase as “an investment” for the job, Ajche said.

What can the fire department do?

In some cases, the fire department has issued sanctions to owners related to the storage and improper charging of lithium-ion batteries.

The owners of a multi-unit rental for seniors in Jamaica, Queens, for instance, were cited for allowing a business that was charging and repairing e-bikes in a seventh floor apartment to operate. The owner of a two-family in Greenwich Village was cited for the dangerous practice of plugging multiple batteries into a power strip when they must be individually plugged directly into wall outlets. The owners of a warehouse in The Bronx were cited for failing to keep charging batteries at least three feet apart and for exceeding the safe level of power usage per charging area.

At a restaurant on Ninth Avenue in Hell’s Kitchen, the owners were cited for storing and charging an e-bike that was “not for personal use.” The law allows up to five e-bikes or e-scooters on premises for personal use, but none for commercial use.

Nevertheless, these types of citations are pretty rare. So far this year there have been 191 e-bike battery fires, while the FDNY has hit only 19 property owners with summons and 10 property owners with violations.

That’s because the fire department can issue citations for conditions they witness at properties where they’re already investigating the cause of a fire, but they do not have the authority to proactively inspect properties for improper battery charging based merely on a complaint.

On East 52nd Street, for instance, the apartment where five e-bikes were charging when the fire erupted is leased by a company that also holds leases to 20 other apartments in that same building. As THE CITY reported, the building management had been trying unsuccessfully to evict that company, Corporate Habitat, from all 21 apartments prior to the blaze, citing — among other issues — complaints that the occupants of those apartments were parking “motorcycles” in hallways.

Last week, Chief Fire Marshal Dan Flynn told THE CITY the FDNY has no plans to check out those apartments to see if any more e-bikes are parked inside.

“We don’t have the mandate to inspect individual apartments,” he said. “The fire didn’t affect those apartments.”

As for whether the city should simply ban the charging of these devices in any type of indoor space, the same fire officials who have repeatedly warned about the dangers of lithium-ion batteries are reluctant to take that drastic step.

“That’s a complicated issue because it does straddle that line,” Thomas Currao, the FDNY’s chief of counterterrorism and emergency preparedness, said at a City Council hearing on the issue last week. “We want it to be safe, but we understand that it has a legitimate use.”

What are lawmakers doing?

The Council is considering four bills that would attack this problem in a variety of ways, starting by banning the sale of reused batteries and batteries that are not certified as fire safe by UL Solutions.

Another bill would create a campaign to educate delivery drivers, requiring the takeout apps to spread the word on how to recharge and maintain batteries safely. And another bill would require the fire department to provide the public with real time information on every e-bike fire going forward.

The Council’s fire and emergency management committee is slated to consider the measures.

Councilmember Gale Brewer speaks outside City Hall, Nov. 14, 2022. Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

As for Albany, State Senator Liz Krueger recently announced two bills to address the rising number of fires caused by lithium-ion batteries. Like the City Council bills, Krueger’s legislation would ban the sale of batteries that aren’t tested by labs like UL Solutions and outlaw the secondary market in reconditioned and used lithium-ion batteries. Both bills allow for fines that could reach up to $1,000 per offense.

Both DoorDash and Grubhub told THE CITY that they support working with policymakers to improve worker safety when it comes to e-bikes. “DoorDash wholeheartedly supports common-sense solutions that will help ensure e-bikes are safe, accessible and used responsibly,” a spokesperson for the app said.

A Grubhub spokesperson said, “any legislation related to e-bikes must consider the disproportionate number of New Yorkers who rely on this type of transportation across a wide range of industries, including but not limited to ours.”

Delivery workers, however, worry about what increased scrutiny could mean for them. “It’s ironic that a year ago we were considered heroes,” Solís said in Spanish at the meeting with FDNY officials this summer, “and now the city wants to take these tools essential for our work away.”

At the FDNY event this summer, a question from Brooklyn Council member Shahana Hanif elicited a round of laughter from the Deliveristas in attendance: Do the tech companies offer any guidance about where and how to purchase safe bikes and equipment?

The answer was a resounding no. “They don’t — and that’s part of the problem,” Ajche said.

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.