Development in western Queens (iStock)

Feb. 26, 2021 By Christian Murray

A number of high-profile developers who are profiting from a Trump-era tax break may be forced to pay more in taxes if a bill State Sen. Mike Gianaris is sponsoring becomes law.

The bill, dubbed the Opportunity Zone Tax Break Elimination Act, would scrap a handsome tax break that allows developers who invest in designated “opportunity zones”—such as the Long Island City waterfront and flourishing areas in Astoria—to defer and later avoid paying capital gains taxes.

Gianaris’ bill, first introduced in 2019, is gaining the support of labor and advocacy organizations as well as other state legislators. For instance, 24 organizations signed a new memo Monday supporting the proposal that would end the state tax break.

The bill targets a federal program that allows individuals and corporations to offset capital gains by investing in opportunity zones. The program was established by the Trump administration to spur investment in economically distressed neighborhoods.

Under the federal program, a developer could—for example–sell a large property in Manhattan and then plow those gains into an opportunity zone. The developer’s federal and state capital gains taxes could then be deferred up to seven years by investing in a zone—with a modest cut in the taxes owed.

But more importantly, they would not face any capital gains on the property within the zone if they keep it for more than 10 years.

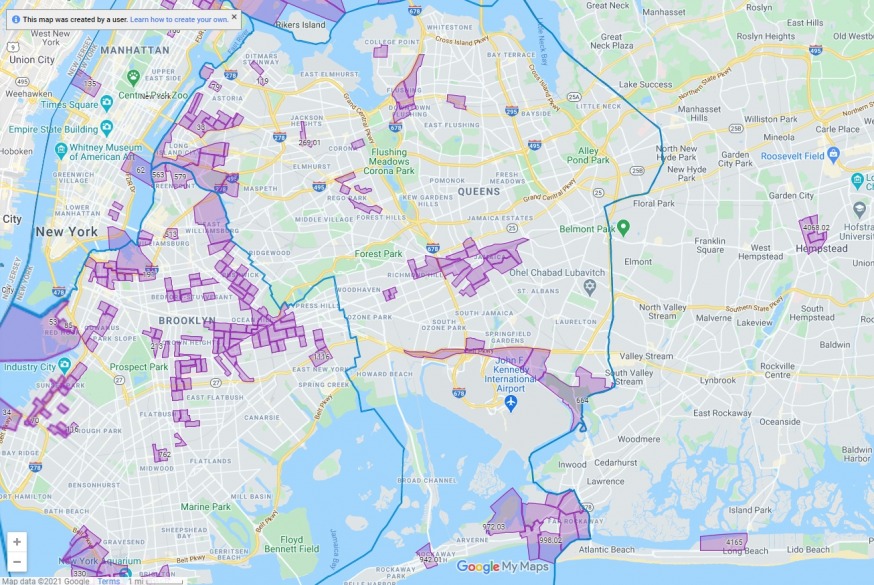

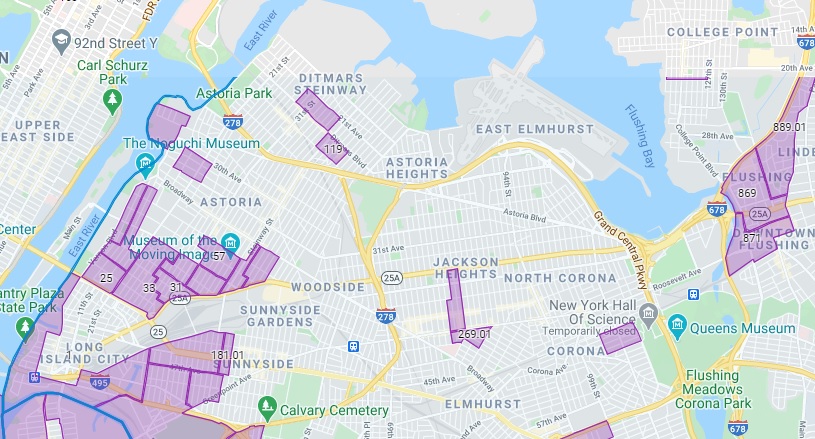

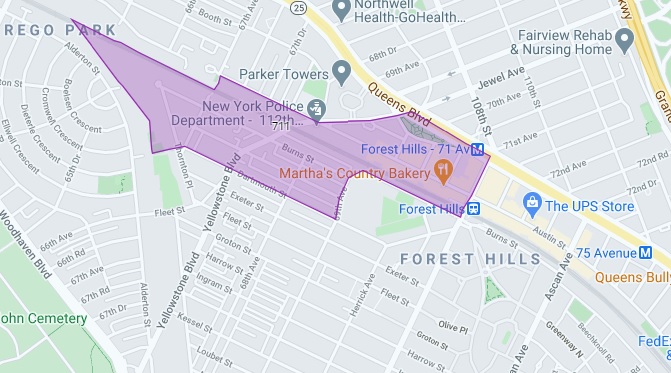

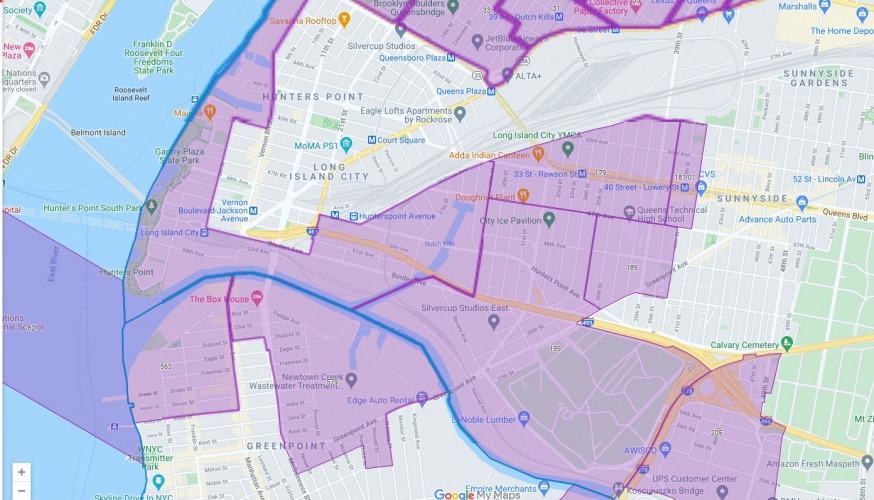

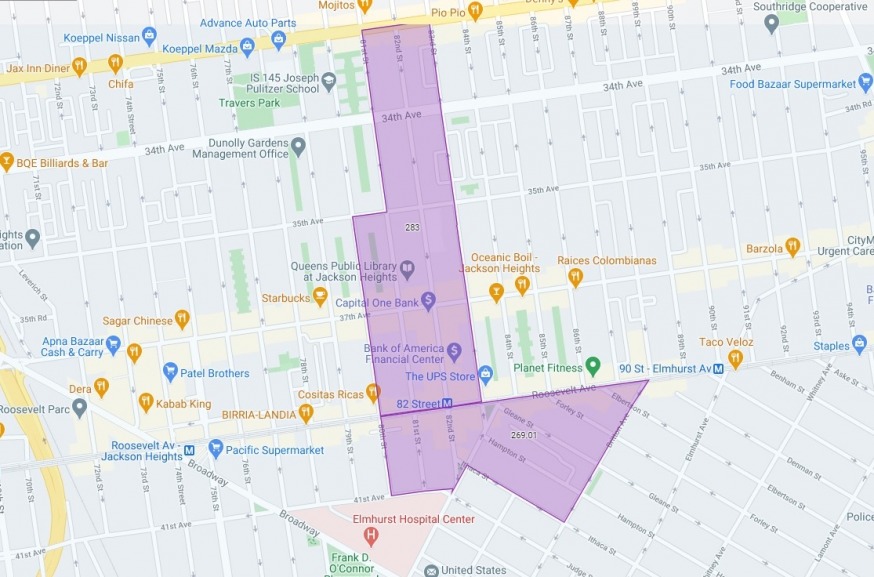

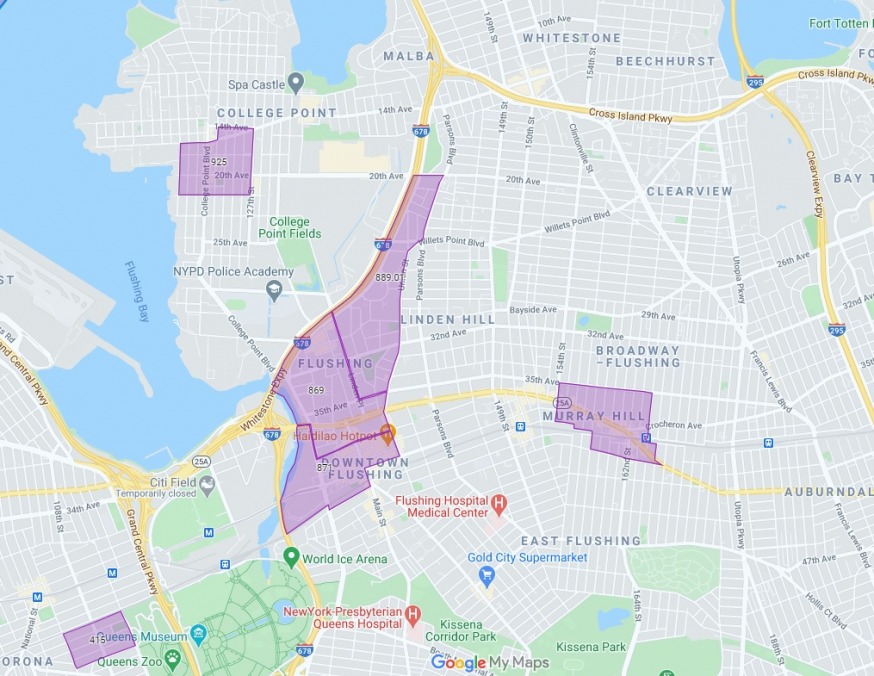

Many of the opportunity zones selected are in areas where massive developments have been going up–or about to go up. They include the Long Island City waterfront, the Flushing Creek, the Astoria waterfront–Hallets Cove peninsula, Austin Street in Forest Hills, 82nd Street in Jackson Heights, Greenpoint Brooklyn and even the Hudson Yards in Manhattan.

The zones were selected by the Cuomo administration in 2018.

New York State Opportunity Zones (Empire State Development Corp. (https://esd.ny.gov/opportunity-zones)

“I don’t know exactly how they came up with the zones—but it smells,” Gianaris told the Queens Post. “There has been massive abuse [with this program].”

The state provides the capital gains tax break in line with the federal government as part of the program.

Gianaris’ bill aims to decouple the benefit, essentially ending the state and city component of the tax break. The capital gains tax in New York State is 8.8 percent plus city taxes.

Under the program, the U.S. treasury identified 2,000 tracts in New York State that were eligible for the designation. The initial list was based on data from the 2011-2015 American Community Survey.

An eligible tract had to have a poverty rate greater than or equal to 20 percent, or have a median family income less than 80 percent of the median for its metropolitan area.

From that list, the governor, via the Empire State Development Corp., was given the authority to determine the Opportunity Zones—comprised of no more than 25 percent of the tracts that the U.S. treasury provided.

The state could also designate some zones that were adjacent to eligible tracts, subject to conditions. The number of such zones was limited to 5 percent– or 100 zones.

One area that was selected that fell outside the eligible tract was the Long Island City waterfront. The zone does not meet the eligibility requirement but it is adjacent to NYCHA housing.

New York State Opportunity Zones (Empire State Development Corp. (https://esd.ny.gov/opportunity-zones)

“It’s not right that Hunters Point is included because it just so happens to be located next to Queens Bridge Houses,” Gianaris said, who is slowly gathering support for the bill.

Many high-profile developers have likely taken advantage of the program.

For instance, developers such as Larry Silverstein plowed big sums into buying underutilized properties by 35th Avenue and Steinway Street in 2019—part of an opportunity zone.

Silverstein in 2020 unveiled plans—as part of a consortium– to redevelop those parcels. The plans, dubbed Innovation QNS, call for 2,700 apartments as well as retail and office space.

Many areas that were already undergoing significant development were declared opportunity zones.

Durst Organization bought property on Hallets Cove in Astoria 2014, where its megadevelopment is going up. In 2018, that small area on the peninsula was carved out as an opportunity zone.

Durst also bought the Clocktower site in Long Island City in 2016, which is also incorporated as part of a zone.

“The Opportunity Zone program was intended to help economically distressed areas but is being abused to grant tax breaks to already overdeveloped neighborhoods,” Gianaris said.

“At a time when the state budget is in dire straits, a giveaway to wealthy developers is the last thing we need.”

Gianaris’ legislation would have no effect on the program itself—since it is a federal program and the federal capital gains would be unaffected.

The legislation is backed in the state senate by Jamaal Bailey, Brad Hoylman, Robert Jackson, Liz Krueger, Zellnor Myrie, Jessica Ramos, Gustavo Rivera, and Julia Salazar.

It has the backing of Jeffrey Dinowitz in the Assembly.

“If there were ever a time for New York to stop giving away tons of money to the super wealthy, this is the year to do it,” Dinowitz said.

“It is outright foolish for New York state to forego this tax revenue so that high-powered and well-connected real estate developers can make extra profits on projects that they were more than likely already in the process of building.”

The opportunity zones will remain in effect until at least 2026. The time frame is deemed too long by critics of the program.

New York State Opportunity Zones (Empire State Development Corp. (https://esd.ny.gov/opportunity-zones)

“This is problematic for two reasons,” according to Sean Campion, who wrote a report on opportunity zones in 2019 that was released by the Citizen’s Budget Commission. “First eligibility was based on data from the 2011-2015 American Community Survey, which was already outdated at the time of selection. Second the opportunity zone boundaries will not adjust to account for neighborhood change and development over time.”

The real estate industry, however, is pushing back against Gianaris’ legislation.

The Real Estate Board of New York, a trade organization that represents large developers, says Gianaris’ proposal is misguided and says that this is a bad time to introduce such legislation. It also says the tax beak could be modified as opposed to being scraped.

“At a time when we need more jobs, more housing and more investment…this legislation takes us in the opposite direction and puts New York at a competitive disadvantage,” a REBNY spokesperson said in a statement.

“We are in an economic crisis in which, for example, citywide construction activity has hit its lowest level in nearly a decade,” the spokesperson said. “If the program needs modifications, they should be considered. But why would we discourage investment in historically underserved neighborhoods?”

New York State Opportunity Zones (Empire State Development Corp. (https://esd.ny.gov/opportunity-zones)

A small piece of Jackson Heights carved out as an Opportunity Zone

Flushing Creek was designed as an opportunity zone